Are you sitting comfortably? Theatre tickets are about to break the four-figure barrier

As Broadway’s star-led productions push ticket prices to new extremes, London holds onto its tradition of accessibility – just. Olivia Cole takes a look at the spiralling cost of seeing great theatre on both sides of the Atlantic

In 1998, on my first trip to the US, I celebrated my birthday by seeing Paul Simon’s The Capeman. Bought in Times Square, the tickets cost a lot but we were a few rows back in the Orchestra – the only annoying thing on the night was someone whispering throughout. It turned out to be Simon himself, giving notes to an assistant. As we sat back down after the interval, he leaned across my now signed Playbill programme, and asked, ‘So whaddaya think? Now you know what you know?’

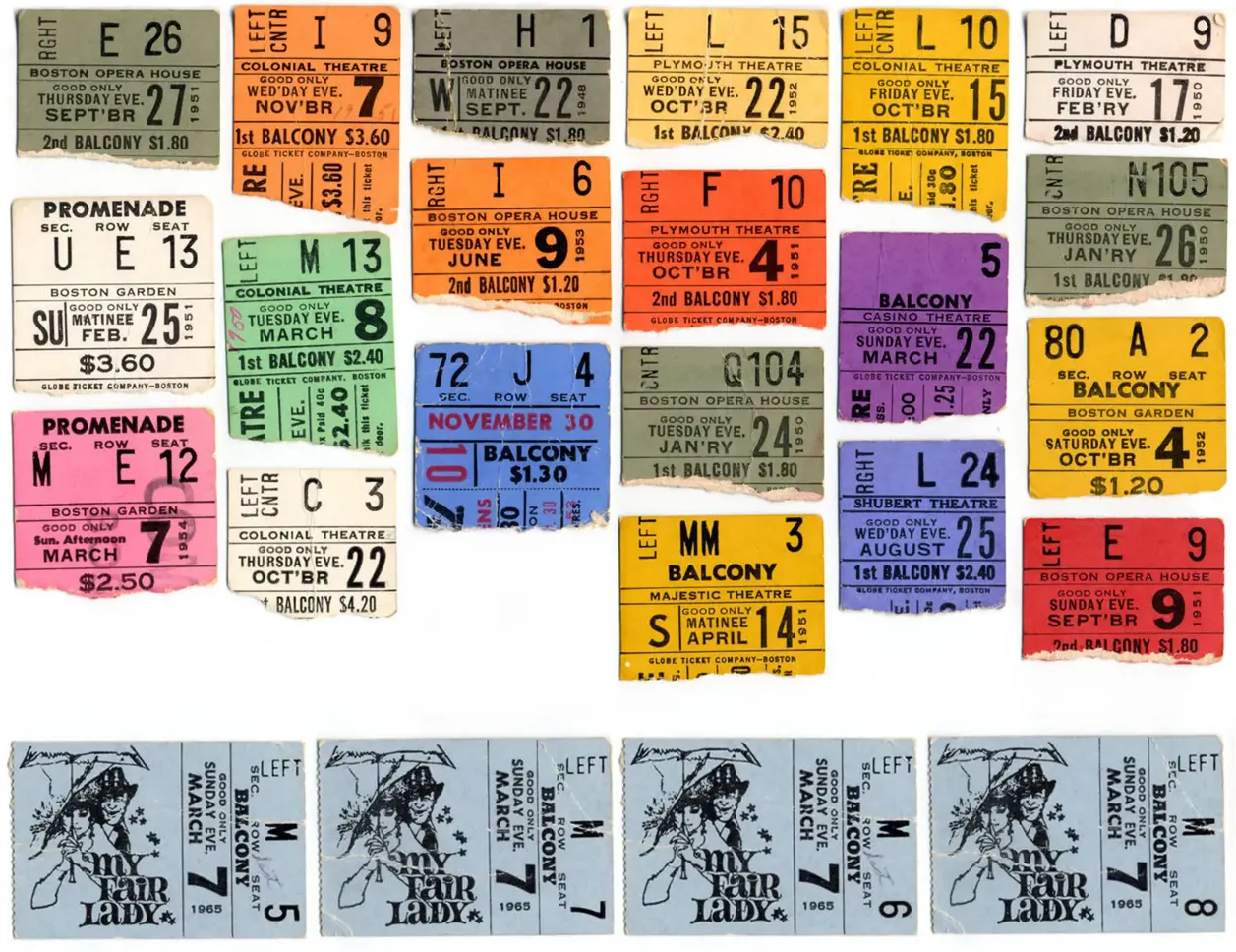

Today, thanks to a live stream on CNN, we can all claim to have seen George Clooney on Broadway in Good Night, and Good Luck, the theatrical version of the film he directed and co-wrote about the journalist Edward R. Murrow holding power to account. A welcome move when theatre tickets have reached record levels; I can’t believe I met Paul Simon, but also, having found the stubs recently, I can't believe the tickets were ‘only’ $68.

There is the headline-grabbing $897 for Othello with Denzel Washington, but $775 for the top price ticket to see Clooney isn’t far behind; these two shows have broken the records as the highest-grossing shows per week in Broadway history. Nevertheless, in London, attendance is back to pre-pandemic levels and in New York, it’s almost there too.

Broadway has always been a different marketplace to London, where ‘it’s expected that you pay more’, says Nick Allott, who opened blockbuster West End shows including Cats, Phantom of the Opera and Les Misérables in his stellar career with Cameron Mackintosh. For Hamilton, which debuted in 2017 (and is still running), he recalls, ‘We had a premium price of £300 and we got a lot of criticism for that. But it enabled us to have two rows of seats at £10 each. Where you have a high top-end, you have to find a low-end.’

The most expensive tickets are driven by research into sales on the secondary-market websites, hence Hamilton then setting the $900 mark for premium tickets on Broadway which is what people were willing to pay. ‘I remember,’ jokingly saying, ‘I could take out an ad in New York, saying it’s cheaper to fly to London, book a hotel, have dinner and see Hamilton in London than it is to go and see it in New York,’ says Allott.

‘There is now no glass ceiling,’ says Matt Wolf, who has covered theatre for The New York Times through decades of rising ticket and production costs. On Broadway, the $100 glass ceiling he identifies was broken by two famous productions: Nicholas Nickleby (1981), which was a transfer from London, and The Producers (2001). Fast forward to today and the acceptable rate is 'whatever the market can bear’ and across both Broadway and London’s West End, ‘anything in double digits is considered cheap’. Wolf maintains Broadway is currently ‘in thrall to An Experience with a capital E, which is seeing a movie star in real life on stage.’ Recovery from the pandemic has been ‘slower, and more painful’ in New York than in London, which can explain the tendency to cater to the wealthy theatregoers who, in relatively small numbers, can afford to keep the business afloat.

But Allott argues it’s not a sustainable model and ‘we’d never get away with the $900 ticket here’. Broadway can be brutal for producers, too. ‘The Tony [awards] determine most new shows’ future and an absence of nominations leads to a slew of closures.’ By contrast, London productions can be a lot more attractive to US investors. The costs are significantly lower and there is ‘good tax relief issued post-Covid and enshrined by both governments since then’.

There’s also a different tradition in the UK, with stars appearing in smaller venues and supporting their very existence by doing so. Ralph Fiennes, off the back of a Best Actor Oscar nomination for Conclave, has a director/star season opening this month at Theatre Royal Bath, helping a venue that – like all of them – has had a shaky few years. He has even signed up Francesca Annis to reunite with him on stage, 30 years after their Almeida Theatre Company’s Hamlet at the Hackney Empire, and Patti Smith appearing for one night. The priciest tickets are around £60; a very welcome figure compared to three figures in London.

Incredibly, London’s not-for-profit spaces have stayed reasonably priced, even with their tiny capacities: just 325 at the Almeida (which Fiennes helped rebuild in the 1990s), and 25 at the Donmar, put securely on the map by Sam Mendes’s stellar decade there between 1992 and 2002, and his successor Michael Grandage. Audience accessibility is part of their DNA, with tickets reserved for younger audiences. Likewise, Grandage’s own company today and the Jamie Lloyd Company. ‘If you don't do that, you'll kill the next generation,’ says Allott. His own formative theatre experiences were after hours spent queuing with an erudite, eccentric aunt to watch RSC history plays up in the balcony. For my part, it was Mendes’ productions at the Donmar for which, as a student, I would happily spend a day queuing for a cheap ticket. (If memory serves, you could even sit down and ‘study’. Or at least that was my thinking...)

Meanwhile, in the West End today, if you’re flexible on dates, it’s still possible to get tickets for under three figures (even if you aren’t a student any more), but to do that you need to book long before the reviews are in, or any kind of consensus on a hit must-see show has emerged.

Whatever your tickets cost, get saving for interval drinks where, again, there’s no (plastic) glass ceiling. And let’s not forget the merch. It’s the theatrical equivalent of sweets at the check-out. No one really needs a T-shirt or an A Little Life tote bag, but to try to sell a few seems fair enough.

Good to Know

In London’s theatreland this autumn, again, the limited run is the name of the game for the biggest names: check out Alicia Vikander and Andrew Lincoln in The Lady from the Sea at the Bridge Theatre (from 10 September) and Bryan Cranston, Marianne Jean-Baptiste and Papa Essiedu in All My Sons, from 14 November at Wyndham’s Theatre.

The Good Life remixed - A weekly newsletter with a fresh look at the better things in life.

Olivia Cole is a cultural commentator whose work on film, art and literature has been published in GQ, Vanity Fair, The Spectator and The Times.